The modern business world is so digitized that almost every company relies on reliable IT systems. Even short downtimes of servers or critical applications can lead to high financial losses, frustrated customers, and a massive loss of trust.

For this reason, the term “High Availability” (HA) is increasingly coming into focus: IT architectures must be designed in such a fail-safe way that a service continues to run even if individual components fail.

But how do you implement “high availability” in practice? And what strategies help you minimize or completely avoid downtime? In this article, we’ll go into deep detail and highlight concepts, methodologies, and best practices for high-availability server environments.

What is High Availability?

High availability refers to the ability of a system to provide a service or application without interruption for as long as possible. This period is often defined as a percentage – for example, 99.99% per year. This key figure, often referred to as “four nines”, means that a system may only be down unplanned for a few minutes a year. Some industries, such as the financial world or the healthcare sector, demand even higher availability values, as even fractions of a second have enormous consequences here.

However, HA goes far beyond simply measuring downtime. It’s a holistic approach that encompasses all layers of your IT – from hardware and network connections to software and organizational processes. Your goal is to either avoid disruptions completely or to reduce the time to recovery (MTTR – Mean Time To Recovery) to a minimum. To do this, you need a well-thought-out interplay of redundancy, clustering, monitoring and failover mechanisms.

Key figures and SLA requirements

In order to make “high availability” measurable and contractually stipulated, many companies work with service level agreements (SLAs). An SLA specifies what uptime you as an operator must guarantee and what maximum downtime is tolerated.

The following applies: The higher the number of “nines”, the exponentially the effort and costs for redundancy and failover technology increase.

| Availability | Description | Downtime per year | Downtime per month | Typical use case |

| 99.0 % | Two nines | ~ 3 days, 15 hours | ~ 7 hrs 18 min | Internal batch jobs, non-critical test systems. |

| 99.5% | – | ~1 day, 19 hrs | ~ 3 hrs 39 mins | Standard websites, simple file servers. |

| 99.9 % | Three Nines | ~ 8 hrs 45 mins | ~ 43 min. | Standard for SMB servers, email services. |

| 99.95% | – | ~ 4 hrs 22 mins | ~ 21 min. | Important business applications (ERP, CRM). |

| 99,99 % | Four Nines | ~ 52 min. 35 sec. | ~ 4 min. | E-commerce, enterprise solutions, data centers. |

| 99,999 % | Five Nines | ~ 5 min 15 sec | ~ 26 sec. | Banking, telecommunications, medical technology. |

| 99.9999 % | Six nines | ~ 31.5 sec | ~ 2.6 sec. | Military systems, aviation (Safety Critical). |

Important for your planning: It can be extremely difficult to guarantee that last bit of uptime, as virtually every technical component, from RAID controllers to air conditioners, can fail at some point. You therefore have to think carefully about which services really need “Five Nines” and where “Three Nines” (and thus almost 9 hours of maintenance windows per year) are completely sufficient.

Redundancy: The key to resiliency

A cornerstone of high availability is redundancy: the provision of several identical resources so that if one component fails, another one immediately takes over (N+1 or 2N redundancy).

- Server Hardware: Instead of using just one physical host, you have at least two identical machines.

- Network Components: Routers, switches or firewalls are used in the HA network (e.g. VRRP, HSRP).

- Power supply: UPS and redundant power supplies are mandatory. Important: Connect redundant power supplies to separate circuits (A/B feed) to avoid the single point of failure .

- Storage Solutions: RAID configurations or distributed storage systems (e.g. Ceph, vSAN) prevent data loss in the event of disk failure.

Cluster solutions for high availability

Cluster technologies form the technological backbone of most highly available environments. The basic principle is orchestration: Several independent servers (nodes) are logically coupled in such a way that they act externally – i.e. for the client or the application – like a single, robust system (single system image). For this to work, clusters typically need a heartbeat connection to monitor each other and a shared storage or synchronized database that all nodes can access.

Access for the clients is usually via a vIP (Virtual IP). This IP address is not hard-wired to a physical server, but is “floating” and dynamically assigned by the cluster manager to the node that is currently providing the service.

In practice, we distinguish between two operating modes, each of which has specific advantages and disadvantages for your architecture:

1. Active-Active-Cluster (Load Balancing & High Availability)

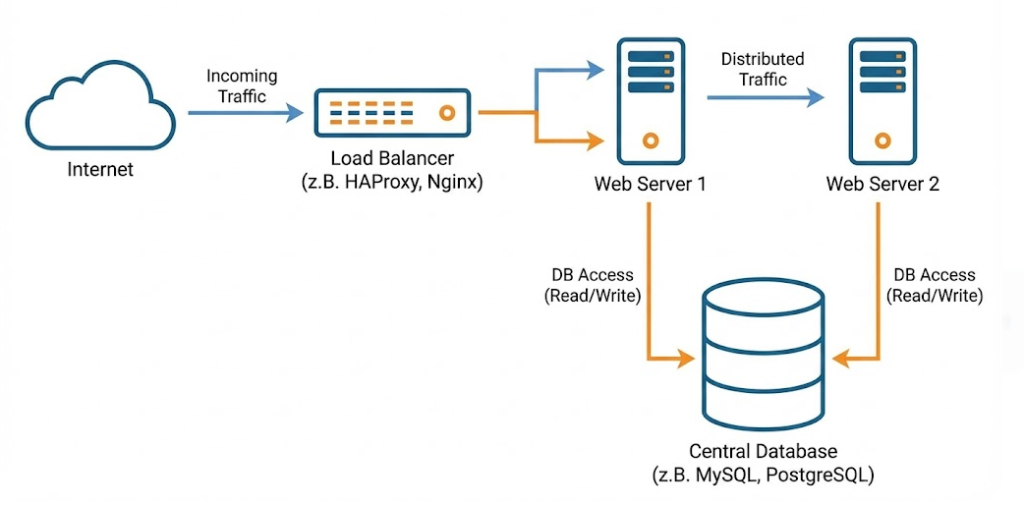

In this scenario, all nodes are active at the same time and process requests. An upstream load balancer (e.g. HAProxy, NGINX or hardware appliances such as F5) distributes the traffic to the available nodes.

- How it works: All servers are running under load. If Node A fails, the load balancer detects this and immediately redirects traffic to Nodes B and C.

- The advantage: You use your hardware efficiently. There is no such thing as a “dead” resource that just consumes power and waits for a failure. In addition, you can perform maintenance work (rolling updates) by removing individual nodes from the load balancer, patching them and inserting them back in one after the other.

- The Trap (Capacity Planning): A common mistake is the miscalculation of the remaining capacity. If you have two servers that are both at 80% capacity, and one fails, the remaining server suddenly has to bear 160% of the load – resulting in an immediate total crash (cascading effect). In a 2-node active-active cluster, you are allowed to use each node to a maximum of 50% to be safe in the event of a failover.

- Area of application: Ideal for stateless services such as web servers, application servers or microservices, as no complex locking mechanisms are required for simultaneous write access to the same database.

2. Active Passive Cluster (Failover Cluster)

Here, a primary node (master/primary) takes over the full load, while one or more secondary nodes (slave/secondary/standby) wait in the background and monitor the state of the primary node.

- How it works: The passive node usually synchronizes continuously with the active node (data replication). If the active node fails (“heartbeat loss”), the cluster resource manager software (e.g. Pacemaker on Linux or Windows Server Failover Clustering) switches the services and the virtual IP to the passive node.

- The advantage: This architecture is often easier to manage, especially for stateful applications. Since only one node writes at a time, you avoid problems with data corruption and complex file-locking mechanisms. Troubleshooting is often more linear.

- The disadvantage: You’re paying for hardware that doesn’t do anything 99% of the time. In addition, there is almost always a short interruption (downtime in the range of seconds) during switching (failover) until the standby node has fully started up the services and taken over the file systems.

- Area of application: The classic for databases (e.g. B. SQL Server Failover Cluster, PostgreSQL with Patroni) or central file servers, where data integrity has absolute priority over maximum performance scaling.

Failover mechanisms: switching in the event of failure

Failover is much more than just a “switch”; it is a highly complex decision-making process that must take place within fractions of a second. If the primary node fails, the system must autonomously decide whether it is a real failure or just a short-lived network problem. To ensure that this “relay race” succeeds without data loss, HA clusters rely on multi-level security mechanisms:

- Heartbeats & Cluster Communication: The nodes monitor each other through regular status signals (“heartbeats”). Technically, this is often solved via Corosync or proprietary cluster interconnects.

- Best Practice: To avoid false positives, you should always route heartbeats through dedicated network interfaces or VLANs (Redundant Ring Protocol), separate from regular traffic.

- Best Practice: To avoid false positives, you should always route heartbeats through dedicated network interfaces or VLANs (Redundant Ring Protocol), separate from regular traffic.

- Split-brain avoidance & quorum: The worst-case scenario in each cluster is the “split brain”. If the interconnect between the nodes is lost, both servers continue to run, but no longer see each other. If both try to take on the “master” role and write to the shared storage at the same time, there is a threat of massive data corruption.

- The solution: A quorum mechanism (voting procedure). A cluster is only capable of acting if it has a majority of the votes (formula:

(n/2) + 1). If you have two nodes, you need an external referee, the so-called tie-breaker or witness (often a small, external file share or virtual instance), who awards the deciding vote.

- The solution: A quorum mechanism (voting procedure). A cluster is only capable of acting if it has a majority of the votes (formula:

- Fencing / STONITH: When a node stops responding, the rest of the cluster must not simply assume that it is off. He could still be stuck in a “zombie status” and write data sporadically. This is where STONITH (“Shoot The Other Node In The Head”), also known as Fencing , comes in.

- The technology: The cluster manager connects directly to the server’s management card (e.g. iDRAC, iLO, IPMI) or a switchable power strip (switched PDU). The faulty node is physically de-energized (hard fencing). Only when the confirmation is available (“node is down”) does the standby node take over the resources and the IP address. This sounds radical, but it is the only way to guarantee 100% data integrity.

Monitoring and proactive maintenance

“Without monitoring, you fly blind” is not an empty phrase in the HA environment, but a risk for business operations. You have to distinguish between the pure “Up/Down” status (ping) and the actual health status of the application (“Application Health”). Tools such as Zabbix, Prometheus, Checkmk or Datadog are industry standards here.

A modern monitoring concept rests on three pillars:

- Holistic metrics (observability): It is not enough to check the CPU and RAM. Critical for HA are:

- I/O Wait & Latencies: Is the database waiting for the hard drive?

- RAID & Hardware Status: Is a controller

Degradedor PSU reporting an error? - Replication lags: How far behind is the passive database node? If the lag is too great, failover may not be possible safely.

- Intelligent Alerting & Escalation: Nothing is worse than “alert fatigue”. A good system filters:

- Warning: Hard drive 80% full → ticket into the system, no nightly malfunction.

- Critical: Cluster service stopped → Immediate notification via PagerDuty, OpsGenie or SMS to the on-call service.

- Automated healing: Scripts (event handlers) that automatically restart the service in the event of known error patterns (e.g. a crashed Apache process) before any human intervention is required.

- Proactive Maintenance & Patch Management: The highest availability is of no use if security gaps make the system vulnerable. HA architectures allow you to patch without downtime through rolling updates:

- You put Node A into maintenance mode (drain), move all workloads to Node B, patch Node A, and restart it. Then repeat the game the other way around.

- Tip: Always test updates first in a staging environment that is identical to production in order to rule out incompatibilities in the cluster network.

Containerization and cloud solutions

Container technologies such as Docker and orchestration tools such as Kubernetes (K8s) have fundamentally changed the concept of high availability. Whereas in the past servers were maintained like “pets”, in modern cloud-native environments they are treated like “cattle“: If an instance fails, it is not repaired, but replaced.

Kubernetes as an HA engine: K8s offers powerful mechanisms for self-healing (self-healing) by default.

- Pod Level: If a container crashes within a pod, the Kubelet service immediately restarts it.

- Node Level: If an entire worker node fails (e.g. due to hardware failure), the K8s Controller Manager detects this, marks the node as “NotReady” and the scheduler automatically reschedules the affected pods on healthy nodes (rescheduling).

- Architecture tip: For true high availability, the control plane (master nodes) must also be redundant (typically 3 nodes), and the worker nodes should be distributed across different fire compartments or zones.

Cloud HA and Auto-Scaling: In the public cloud (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud), you no longer rely on individual hardware, but use Availability Zones (AZs). An AZ is an isolated data center within a region.

- Multi-AZ Deployment: Your application runs in parallel in Zone A and Zone B. If Zone A fails completely (e.g. due to a power failure), the load balancer seamlessly directs traffic to Zone B.

- Auto-Scaling Groups: These are not only used to cope with loads. They are an essential HA building block. A “Minimum Health Check” rule ensures that sick instances are automatically scheduled and replaced with fresh ones without you having to get up at night.

Hybrid approaches: Many organizations use a hybrid cloud to keep sensitive data on-premises , while stateless frontends scale in the cloud. Here, the redundant connection (e.g. VPN in failover with Direct Connect/ExpressRoute) becomes the critical path.

Disaster recovery and geo-redundancy

While High Availability protects you from the failure of individual components, Disaster Recovery (DR) is your life insurance against the total loss of a site (e.g. due to fire, flooding, cyber attack or large-scale power failure). Hierarchically, DR stands above HA and often requires declaring an emergency.

Two key figures are central to your strategy:

- RPO (Recovery Point Objective): What is the maximum amount of data you can lose? (e.g. “Data status from 15 minutes ago”).

- RTO (Recovery Time Objective): How long can the system be idle until it runs at the second location? (e.g. “Restore within 4 hours”).

Geo-redundancy and replication types: To achieve true geo-redundancy, data centers should be far enough apart (often >100 km) not to be affected by the same disaster. The distance dictates the technique:

- Synchronous replication (campus cluster): Data is written to site A and B at the same time. The write process is not considered complete until both confirmations are available.

- Advantage: RPO = 0 (No Data Loss).

- Disadvantage: Requires extremely low latency (Dark Fiber), otherwise the performance of the application will suffer. Usually only practicable up to a distance of about 10–50 km.

- Asynchronous replication (geo-cluster): Data is first written locally and then transmitted to the remote location in the background.

- Advantage: Works over any distance without sacrificing performance.

- Disadvantage: RPO > 0. In the event of a disaster, the data of the last seconds or minutes that were still “in the cable” is missing.

Cloud backup as a DR strategy: Not every company can afford a second physical data center. The cloud offers attractive models here:

- Cold Standby (Backup & Restore): Data is stored as a backup in the cloud (e.g. S3 / Blob Storage). In an emergency, VMs are only then booted up and the data imported. Cheap but high RTO.

- Pilot Light: Databases are running synchronized on a low flame in the cloud, application servers are down. In an emergency, the app servers are started and the database is scaled up. A good compromise between cost and speed.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Safety Curve

A system with 100% availability is a theoretical construct – in practice, it is technically impossible and economically nonsensical. The closer you get to the “five nines” (99.999%), the more exponentially the cost of hardware, licenses, and personnel increases.

As an administrator or architect, you often have to act as a consultant for the management. The central question is not “What is technically feasible?”, but “What does the failure cost us?”. This is where a Business Impact Analysis (BIA) can help.

- Scenario A: The internal file server is down for 2 hours. Annoying, but the workforce can continue to work locally or take a coffee break. -> Cost risk: Low. A simple RAID and a daily backup are sufficient (SLA ~99%).

- Scenario B: The webshop of an e-commerce giant is at a standstill for 2 hours on Black Friday. -> Cost risk: Extremely high (loss of sales + damage to image). A geo-redundant active-active cluster (SLA 99.99%) is worthwhile here.

The rule of thumb: The investment in high availability (HA) and disaster recovery (DR) must never exceed the potential cost of an outage. It is often sufficient to establish maximum redundancy for business-critical core services (“Tier 1”), while test or archive systems (“Tier 3”) are allowed to be offline for a day.

Team and organization: The human factor

Even the most expensive hardware is useless if panic breaks out in an emergency. A high-availability system is kept alive not only by technology, but above all by processes. The most common cause of downtime today is no longer hardware defect, but human error (misconfiguration).

A mature HA concept therefore necessarily includes:

- Runbooks & Documentation: Knowledge must not only exist in your head. Create “emergency runbooks” that explain step-by-step what to do if component X fails. These must be written in such a way that even a colleague from the on-call service who did not build the system can understand them at 3 a.m.

- Regular “Fire Drills” & Chaos Engineering: Don’t wait for the emergency. Test the failover!

- Basic: In the maintenance window, pull the network cable from the primary node. Will the IP change course?

- Advanced: Use “chaos engineering” methods (such as the Netflix Chaos Monkey) to randomly inject disturbances on the fly and harden the resilience of your architecture.

- Post-mortems: If there has been a bang, the question of guilt is irrelevant. Perform Blameless Post-Mortems. Analyze the incident technically (root cause analysis) to understand why the failover didn’t work or why the monitoring didn’t alert, and improve the system for the future.

- Training: Technologies are changing. If you run a Kubernetes cluster, you need different knowledge than for a Windows failover cluster. Make sure your team is fit for the technologies used.

Result

High Availability is not a product you buy and screw into the rack. It is an architectural philosophy and an ongoing process. By intelligently using redundancy (no single point of failure), cluster technologies (Pacemaker, K8s) and clean failover mechanisms (STONITH, Quorum), you can drastically minimize downtime.

But never forget: technology is only the tool. Real availability comes from clean planning, constant monitoring and a team that has practiced the emergency. Geo-redundancy and cloud solutions are powerful extensions to be prepared for disasters.

Your HA checklist to get started:

- [ ] SPOF analysis: Are there components (router, power supply, switch) whose failure paralyzes everything?

- [ ] Redundancy: Is N+1 guaranteed everywhere (power, cooling, compute)?

- [ ] Monitoring: Are not only “pings” monitored, but also application health and disk space?

- [ ] Backups: Do the backups work AND (more importantly) have the restores been tested?

- [ ] Failover test: When was the last time you pulled the plug to see if the standby server really took over?

- [ ] Documentary: Is there an up-to-date emergency manual?

The more ticks you can put here, the more peacefully you will sleep – even if the pager is silent.

further links

| BSI IT-Grundschutz – Standards for emergency management and availability | https://www.bsi.bund.de/DE/Themen/Unternehmen-und-Organisationen/Standards-und-Zertifizierung/IT-Grundschutz/it-grundschutz_node.html |

| ClusterLabs – The one-stop shop for Linux High Availability (Pacemaker/Corosync | )https://clusterlabs.org/ |

| Kubernetes Documentation – Concepts for Cluster Architecture and Self-Healing | https://kubernetes.io/de/docs/concepts/architecture/ |

| Atlassian Incident Management SLA and Time Metrics (RPO/RTO) Explained | https://www.atlassian.com/de/incident-management/kpis/sla |

| Prometheus Monitoring – Open-source monitoring for reliable metrics | https://prometheus.io/ |